I am a huge fan of Jeff Bezos and admire his financial skills hugely!! Yes, while he is one of the greatest tech entrepreneurs of all time who has revolutionized the retail industry for decades to come; his financial acumen is exemplary. Had written about Jeff’s business acumen previously in a detailed blog post here!!

In his FY2004 letter to shareholders, he illustrated an example wherein some of the investing myths regarding Earnings, EBITDA, shareholder value creation, valuation – all got busted via this.

Most of the below is being reproduced from the letter itself (being highlighted for greater emphasis from my side)

Our ultimate financial measure, and the one we most want to drive over the long-term, is free cash flow per share.

Why not focus first and foremost, as many do, on earnings, earnings per share or earnings growth? The simple answer is that earnings don’t directly translate into cash flows, and shares are worth only the present value of their future cash flows, not the present value of their future earnings. Future earnings are a component—but not the only important component—of future cash flow per share. Working capital and capital expenditures are also important, as is future share dilution.

Though some may find it counterintuitive, a company can actually impair shareholder value in certain circumstances by growing earnings. This happens when the capital investments required for growth exceed the present value of the cash flow derived from those investments.

To illustrate with a hypothetical and very simplified example, imagine that an entrepreneur invents a machine that can quickly transport people from one location to another. The machine is expensive (Jeff is talking about Blue Origin, his personal space shuttle venture, enabling passengers to go from earth to moon and back) – $160 million with an annual capacity of 100,000 passenger trips and a four-year useful life. Each trip sells for $1,000 and requires $450 in cost of goods for energy and materials and $50 in labour and other costs.

Continue to imagine that business is booming, with 100,000 trips in Year 1, completely and perfectly utilizing the capacity of one machine. This leads to earnings of $10 million after deducting operating expenses including depreciation—a 10% net margin. The company’s primary focus is on earnings; so, based on initial results the entrepreneur decides to invest more capital to fuel sales and earnings growth, adding additional machines in Years 2 through 4.

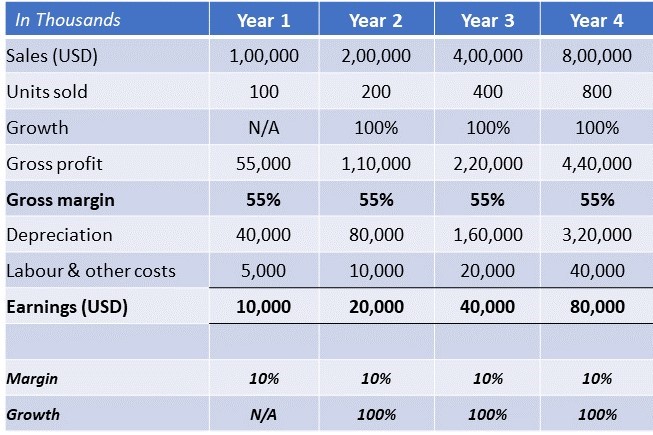

Here are the income statements for the first four years of business:

It’s impressive: 100% compound earnings growth and $150 million of cumulative earnings. Investors considering only the above income statement would be delighted.

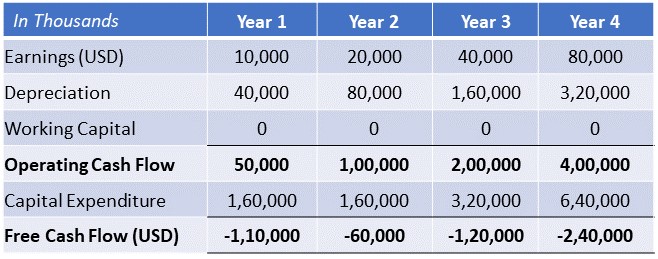

However, looking at cash flows tells a different story. Over the same four years, the transportation business generates cumulative negative free cash flow of $530 million.

There are of course other business models where earnings more closely approximate cash flows. But as our transportation example illustrates, one cannot assess the creation or destruction of shareholder value with certainty by looking at the income statement alone.

Notice, too, that a focus on EBITDA—Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization—would lead to the same faulty conclusion about the health of the business. Sequential annual EBITDA would have been $50, $100, $200 and $400 million—100% growth for three straight years. But without taking into account the $1.28 billion in capital expenditures necessary to generate this ‘cash flow,’ we’re getting only part of the story—EBITDA isn’t cash flow.

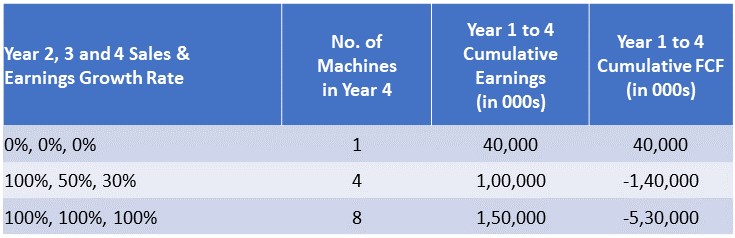

What if we modified the growth rates and, correspondingly, capital expenditures for machinery – would cash flows have deteriorated or improved?

Paradoxically, from a cash flow perspective, the slower this business grows the better off it is. Once the initial capital outlay has been made for the first machine, the ideal growth trajectory is to scale to 100% of capacity quickly, then stop growing. However, even with only one piece of machinery, the gross cumulative cash flow doesn’t surpass the initial machine cost until Year 4 and the net present value of this stream of cash flows (using 12% cost of capital) is still negative.

Unfortunately, our transportation business is fundamentally flawed. There is no growth rate at which it makes sense to invest initial or subsequent capital to operate the business. In fact, our example is so simple and clear as to be obvious. Investors would run a net present value analysis on the economics and quickly determine it doesn’t pencil out. Though it’s more subtle and complex in the real world, this issue—the duality between earnings and cash flows—comes up all the time.

Cash flow statements often don’t receive as much attention as they deserve. Discerning investors don’t stop with the income statement.

Since the transportation Blue Origin business if flawed right now, thankfully, Jeff is not buying the rockets through Amazon’s core business, unlike some entrepreneurs who use shareholder’s money to buy shiny toys for themselves at the garb of superfluous EBITDA!!

Disclaimer: Please note that these are my personal views. While I am NOT a registered Research Analyst as per SEBI (Research Analyst) Regulations, 2014, all investors are advised to conduct their own independent research into individual stocks or industries before making any decision. In addition, investors are advised that past stock performance is not indicative of future price action.

Pingback: Jaagravisms – Part I – Jaagrav